In this post series, I will explain each of Teddy’s diagnoses in detail, with more medical terms and imaging if I am able to find them. These will be long and more technical posts, but for those interested, we hope it will educate more people on these rare conditions, so as the rate increases each year, there are more people out there familiar with these diagnoses who can help and educate themselves and others. Please feel free to ask questions and I will do my best to address them. For today’s post, most of the technical information is copied directly from the Boston Children’s website.

After Teddy’s birth, the very first official diagnosis he received was Esophageal Atresia and Tracheoesophageal Fistula (EA/TEF). Upon his initial assessment, the doctors quickly realized his esophagus and airway did not form correctly. This diagnosis required Teddy to have surgery at 16 hours old and was the reason for most of Teddy’s surgeries and major complications. In this post, I will give a more educational medical discussion about the diagnosis and how it has affected Teddy specifically. For the diagnosis, I will be taking explanations directly from Children’s hospitals website and will provide links, so you are able to research as well.

EA/TEF is considered a rare diagnosis, with about 1 in every 4,000 births (3,000 – 5,000 depending on the research). While this is rare, the occurrence of this defect has increased significantly over the years, as have the treatment options and survival rates. Even since Teddy’s birth, the new surgical treatment options have grown with more innovative and minimally invasive options.

Boston Children’s Hospital (Esophageal Atresia | Boston Children’s Hospital (childrenshospital.org) describes EA/TEF: Esophageal atresia (EA) is a rare birth defect in which a baby is born without part of the esophagus (the tube that connects the mouth to the stomach). Instead of forming a tube between the mouth and the stomach, the esophagus grows in two separate segments that do not connect. In some children, so much of the esophagus is missing that the ends can’t be easily connected with surgery. This is known as long-gap EA. EA frequently occurs along with tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF), and as many as half of all babies with EA/TEF have another birth defect, as well. Without a working esophagus, it’s impossible to receive enough nutrition by mouth. Babies with EA are also more prone to infections like pneumonia and conditions such as acid reflux. Luckily, EA is usually treatable. There are four types of esophageal atresia (EA) (visual representation attached):

- Type A. The upper and lower segments of the esophagus end in pouches, like dead-end streets that don’t connect. Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) is not present.

- Type B. The lower segment ends in a blind pouch. TEF is present on the upper segment. This type is very rare.

- Type C. The upper segment ends in a blind pouch. TEF is present on the lower segment. This is the most common type.

- Type D. TEF is present on both upper and lower segments. This is the rarest form of EA/TEF.

The exact cause of EA is still unknown, but it appears to have some genetic components. Up to half of all babies born with EA have one or more other birth defects, such as:

- trisomy 13, 18 or 21

- other digestive tract problems, such as intestinal atresia or imperforate anus

- heart problems, such as ventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, or patent ductus arteriosus

- kidney and urinary tract problems, such as horseshoe or polycystic kidney, absent kidney, or hypospadias

- muscular or skeletal problems

- tethered spinal cord

EA and TEF are also often found in babies born with VACTERL (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheo-esophageal fistula, renal anomalies and limb abnormalities) syndrome. Not all babies born with VACTERL syndrome have abnormalities in all of these areas. Teddy would eventually be diagnosed with VaCTERL, since no genetic causes were found, which I will explain further in a future post.

Although EA can be life-threatening in its most severe forms and could cause long-term nutritional concerns, the majority of children fully recover if it’s detected early. The best treatment for EA is usually surgery to reconnect the two ends of the baby’s esophagus to each other. For many children, this surgery can take place within the first few days or weeks after birth. For those with long-gap EA, however, it can take months or years to be able to fully repair the esophagus. Even after repair, however, many (if not most) have long-term effects related to EA/TEF such as barky cough, esophagus strictures, limited esophagus motility, reflux, etc. As we get closer in the story to Teddy’s repair surgeries, I will do a separate post to describe the surgical options much more thoroughly for those who are interested.

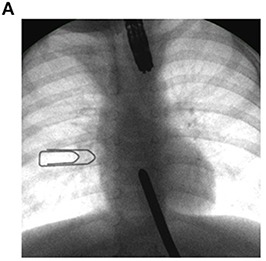

Esophageal atresia (EA) is usually diagnosed shortly after birth when an infant exhibits symptoms such as coughing, choking, and turning blue when trying to feed. If the physician is unable to pass a feeding tube all the way into the child’s stomach through the nose or mouth, this is a sign of EA, which was the case for Teddy. This diagnosis is then typically confirmed with x-rays. Sometimes, EA is identified before birth if the mother’s ultrasound shows too much amniotic fluid or an “absent stomach,” which is a sign of this disorder.

With all the ultrasounds and doctor appointments prior to birth, EA/TEF was never mentioned as a possible diagnosis. Looking back, Teddy had all of the classic signs, where EA should have been diagnosed prior to his birth, but it was missed. His stomach bubble was tiny or often not seen and I had severe Polyhydramnios (too much amniotic fluid). With that said, those same signs could be related to a number of different diagnoses, so we do not blame the doctors for missing that possible diagnosis, which would not have changed his birth or immediate need for surgery, but it could have given us the option to plan to give birth at a much larger hospital chain that specializes in treating EA/TEF and potentially prevented many of the challenges he faces in his first few months. Hindsight is 20/20 though, so realistically, who knows what would have happened or been different.

After rounds of imaging and internal examination, Teddy was diagnosed with Type C long gap EA/TEF. It is the most common form of EA, however, the longer the gap, the rarer it gets. For our local hospital, which saw a few cases a year, Teddy’s gap was one of the longest they have seen, with his top pouch ending just below his jawline. They estimated it was approximately a 6 centimeter (2.3 inch) gap (we would later find it was actually 4 cm (1.5 inch), which was a great thing and opened the door for more treatment options). This meant that Teddy would not be able to receive surgery right away and would need to be on continuous suction to keep him from aspirating on the secretions he made in his mouth since they were unable to go into his stomach. Going back through all our 1000s of pictures, we somehow do not have a clear picture of his esophagus imaging prior to his reconnection. I was honestly shocked by this because we have so so many pictures, but we will have actual imagining for other diagnoses. I was also unable to download them from his mychart accounts.

What I do have pictures of is how we managed his EA/TEF until his reconnection surgery, which are attached below. In his very first surgery, the surgeon went through his side (thoracic) and was able to remove the bottom portion of his esophagus from his airway and seal both the airway and esophagus pouch. This prevented him from aspirating on stomach fluids/food and also prevented air from filling his stomach. He also received a g-tube (gastronomy tube), which allowed him to be fed through the tube straight into his stomach. To manage the upper pouch of his esophagus, when first born and required oxygen support, a suction tube that was set to continuous suction was placed into his mouth. Later after he no longer needed oxygen, we were able to place the tube through his nose, to help reduce long-term oral aversions. Our local hospital recommended the “wait for it to grow” approach, meaning as he got bigger, in theory, his pouches would get bigger and then be stretched to reconnect. Or we could opt for a “spit fistula” which meant his upper pouch would be connected to an opening in his neck for open drainage, so suction was not needed, and then when he was older he could get additional surgeries to try and connect the two ends.

I will go into more details related to our choices as I write his story, but at the time with only the options our local doctors were giving us, we decided to go with the “wait for it to grow” choice, which meant he would need to stay on continuous suction. As we did more research and found other parents who had children with EA, we quickly realized that the hospital your child is in makes a MASSIVE difference as to the future success of their treatment, especially the more rare the condition. We are so very grateful and thankful for all the doctors and surgeons at our local hospital, but we came to realize that Teddy needs to be somewhere else to give him the best chance at survival and quality of life. So we eventually transferred to Boston Children’s Hospital, which has a highly specialized team specifically for EA/TEF, for all of his EA treatment.

Without our natural inquisitive nature, understanding of how to research, and desire to find a supportive community, Teddy’s story would be very different. I hope that through Teddy’s story and all of our supporting posts, we will be able to help educate others on these rare conditions. It is so easy to just blindly follow a doctor’s advice because you do not know any better. While that advice might be the absolute best choice that doctor has to offer, if they are not a specialist and see thousands of similar cases a year, they likely are not the best options the medical world has to offer. So please always research, always search for parent support groups and also help those in similar situations who may not have access to the same kind of support and information. The more we can share and support, the better chance babies born with rare conditions will have at receiving the best possible treatment for the best possible outcome.

If you know someone who has been recently diagnosed with EA/TEF, I urge you to encourage them to reach out to top Children’s Hospitals that specialize in this condition. Some of the top hospitals right now for EA/TEF are Boston, Cincinnati, CHOP (Philadelphia), and John Hopkins All Children (St. Petersburg). There are many more out there, but these are the ones you will hear the most about from parent groups. If nothing else, call around for second opinions and urge local surgeons who are not as familiar with this condition to reach out to those who are.

While Teddy’s diagnosis list is very long, EA/TEF has definitely been the most difficult one for many reasons. Almost all of his 13+ hour surgeries and major complications were related to this condition. Thankfully we are past the worst and his esophagus is beautiful, but it was a long, difficult, and scary road to get there that resulted in some of our scariest memories after his birth. Teddy was so strong through it all and continued to show us just how remarkable he is!